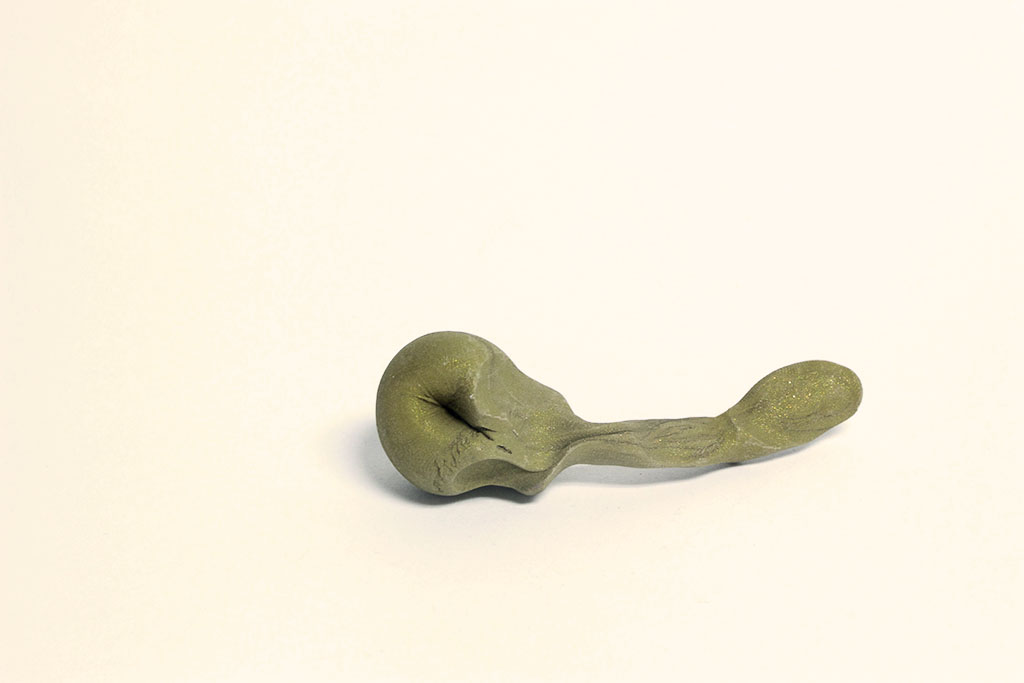

The history of painting in western art is fraught with mythologies centered around the gestural mark. In my own practice, I have begun to view each of those inspired marks, strokes, smushes, and splatters as unique characters captured in a moment on canvas. Each character plays a specific role, as if it were the lead flute player in the orchestra, or supporting actress in the play. Recognizing them in this manner has led to a strong desire to possess each mark in other ways. As I began forming three-dimensional versions of my cast of characters, through clays and plaster, my objects became containable and collectable in new, satisfying ways. I can now more tangibly obsess over them, grouping them and creating paintings in space. Each new composition has become another way to display my collection. Once I started re-inserting them as objects onto the surface of paintings, and permanently attaching them to each other, I found myself longing for their previous, autonomous existence. In response to this longing, a new phase of possession emerged through photography. Each object is now caught candidly in polaroid snapshots, and documented professionally with a studio portrait – providing them all the opportunity to live on simultaneously as revered individuals and cast members performing in painting. There is truth in Jean Baudrillard’s assertion that “the fulfilment of the project of possession always means a succession or even a complete series of objects… [which] is why owning absolutely any object is always so satisfying and so disappointing at the same time: a whole series lies behind any single object, and makes it into a source of anxiety.”

I make these objects out of both a painterly compulsion to obsess over gesture, as well as an uncomfortable need derived from the lens of cultural materialism my generation views the world through. As a young, black female inserting herself into a historical conversation about signification in painterly abstraction, I also see these quirky little forms as subversive in their own right. They exist in multiple formats. They are art objects. They are collectibles. They are toys. They are action figures. They are paint. They are images. They are portraits. They are replicas. They are idiosyncratic. And through every iteration that exists, they are reflections of those original gestures. Despite what the objects in your collection actually are, as Baudrillard says, “what you always collect is yourself.”